Though the Government of Ethiopia is likely to continue its developmental state model, the country is signaling tactic shifts which includes from public to private activities, from capital to current spending, and from debt to equity, a new report reveals.

The report released today by Cepheus Growth Capital Partners, the $100 million private equity investment that entered Ethiopian market recently, argues that Ethiopia won’t change its developmental state model in its fundamental goals or objectives.

“…But surely in the tools and tactics employed. We see economic policy shifting its focus in three areas—from public to private activities, from capital to current spending, and from debt to equity,” says the report, ‘Ethiopia Macroeconomic Handbook 2019’.

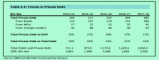

As input the report put together ten questions often raised by investors during discussions of the Ethiopian macro-economy. It included ten years of macroeconomic data with forecasts covering the real, monetary, fiscal and external sectors for 2019 and 2020.

“Since the start of the country’s high-growth phase about 15 years ago, policy priorities have been heavily focused on boosting GDP growth, with massive efforts directed at boosting public investment and raising agricultural output. Budgetary spending, funded partly by enhanced revenue and substantially by new borrowing, was biased towards capital outlays and pro-poor spending in the form of infrastructure and social sector investments,” the report said.

Explaining further the Ethiopian developmental state model, which the country has been following in the past decade, the report listed four main features:

- GDP growth was taken as the over-riding policy priority above all else;

- land ownership was retained in state hands allowing for discretionary allocations to address important policy priorities (e.g., public housing, urban expansion, industrial parks, commercial farm allocations, public roads/infrastructure, etc.);

- the industrial sector was nurtured, shaped, and directed through a range of activist and interventionist tools steering economic activity towards certain priorities and not to others (tax exemptions, industrial parks, directed loans/foreign exchange from state banks); and

- the financial sector was closely regulated to serve developmental policy priorities by mobilizing low-cost savings from large segments of society, raising ‘captive funds’ from the private sector (the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) Bills, private pension funds), and funneling low-cost funds to government, state enterprises, and (partially via the Development Bank of Ethiopia (DBE) to the private sector.

“Judging by the four developmental state ‘markers’ laid out earlier, a fundamental break from that approach to economic development seems unlikely. In particular, we see economic policy-making still guided by a vision that targets high GDP growth (critical to move towards middle income status) and that continues to retain substantial scope—especially compared to the vast majority of African and developing countries—for activist state interventions in land, industrial, and financial policies,” the report said.

The report explained below in detail the four areas:

• Growth: Boosting growth, and the job-creation/income earning opportunities associated with it, remains the fundamental guide for economic policy per repeated policy statements given by the new Prime Minister and administration.

However, it is clear that the type of growth will increasingly be given as much attention, with a greater likely focus on its qualitative dimensions (job/income creation and ultimate impacts on household consumption) as well as its underlying sources (more private-sector and consumption-driven and less debt-reliant)

• Land will continue to remain in state hands for the foreseeable future, in our view, but be made available to the private sector via user rights (in agriculture) and long-term leases (in the urban/commercial sectors).

The status quo provides policymakers extensive discretion in making priority allocations at the federal and regional level—be it for infrastructure, urban expansion, industrial parks, mining projects, commercial farming allocations, and other such projects deemed to be in the broader public interest.

Such a heavy scope in the determination of land allocations is rare in developing countries—but also an undeniably powerful and potentially positive tool for a development-minded government working in the public interest.

• Industry: With respect to the industrial sector, a center-piece of policy initiatives in this area has been and remains the development of 20-plus industrial parks to establish an export-led manufacturing base in Ethiopia.

As only about a quarter of industrial parks have been finalized so far (8 out of 22), 3 and their performance is still in its early stages, we expect close and continued nurturing on the part of the government, including work to simplify the ease of doing business for Industrial-Park based companies (especially in overcoming logistics and labor challenges) and various other hand-holding support until key targets begin to be met.

• Finance: Unlike the openness to foreign capital planned in multiple areas (airlines, telecom, power, logistics), the dominant state bank was notably excluded from consideration for even a partial privatization and Ethiopia’s financial sector remains one of the few worldwide that is closed to foreign investors.

“This signals that directed lending schemes, as is common for a developmental state, will remain an important element of the financial system, though it is important to recognize that various emerging financing sources will also be taking hold at the same time,” the report said.

“Accordingly, we expect various important public-sector directed financing mechanisms—such as the allocation of public pension savings to government financing at low cost, the expansion of DBE, and NBE bills requirement on private banks—to remain in place as they facilitate the mobilization of low-cost funds to priority beneficiaries (including private beneficiaries, it must be noted, as in the case of DBE).”

With respect to the budget, its broad expenditure orientation and priorities—a significant share of pro-poor expenditure focused on delivering key public goods—is also not significantly altered as already seen in the June 2018 passage of the new administration’s first budget.

And finally, Cepheus’ reports argues there are also no indications that the still-closed capital account would be up for opening as policymakers will aim (quite rightly at this stage) to restrict formal capital outflows so they may be channeled to domestic uses instead.