Ethiopia improved its performance in tackling a range of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) between 2015 and 2017, according to statistics released at the African Union Summit.

But the country has been urged to further increase work to eradicate what are widely known as ‘diseases of poverty’. NTDs such as blinding trachoma, the leading cause of infectious blindness, or intestinal worms that can stunt growth in children, are endemic in poor communities without access to clean water and with inadequate sewerage systems.

NTDs are known as ‘diseases of poverty’ because they thrive in poor communities and trap people in a cycle of extreme difficulties including not being able to go to school or work.

The other three of the five most common NTDs are mosquito-borne elephantiasis (also known as lymphatic filariasis); snail-borne bilharzia; and river blindness. These five diseases affect 1.6 billion people worldwide – one in five on the planet – including over 600 million people in Africa.

All five NTDs can be prevented or treated with medicines that are donated for free to endemic countries by pharmaceutical companies.

The new statistics were released for the meeting of the African Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA) forum, which since 2018 has been monitoring African countries’ actions against the five most common NTDs. ALMA calculates an Index score for each endemic country’s fight against the diseases. This is used to construct the League Table attached.

The NTDs Coordinator for Ethiopia, Nebiyu Negussu said: “A positive factor is that in recent years we have been able to increase funding for NTDs from domestic resources as well as obtain new donor finance, particularly for the fight against blinding trachoma”.

“But there is still plenty of work to do”, Mr Negussu added;

“We had planned to complete the mapping of the extent of river blindness in 2018 but didn’t complete this partly because the WHO guidelines changed, which complicated the task”.

“However, we are now building towards our ‘Third Master Plan’ which is aiming for elimination”, the Ethiopian NTD Coordinator concluded;

“Before 2020 we aim to finish mapping and many other activities. Our ambition is now not just mapping but also 100% geographical coverage and delivering an enhanced quality of service to accelerate the elimination of NTDs”.

NTDs rarely make headline news because they tend to afflict the poorest and most marginalised communities. The diseases were once prevalent throughout the world, including in western countries. But they are now almost exclusively endemic in developing nations. They cause disability and stigma and can even lead to death.

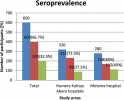

The number of people in Africa in need of treatment for NTDs has fallen since 2015, the year world leaders adopted the sustainable development goals in which NTDs were specifically mentioned as a target. Over the same period, the proportion of people receiving treatment compared to those in need, has risen.

In Sub-Saharan Africa alone, there were 630 million people in need of treatment for at least one NTD in 2015. By 2017 this had fallen to 605 million – a drop of 25 million in just three years, showing that treatments for NTDs are effective.

This is a step in the right direction towards meeting the sustainable development goal for NTDs, which is to reduce the number of people in need of treatment for NTDs by 90% by the end of 2030.

In 2015 the proportion of the 630 million people in need of treatment in Sub Saharan Africa who received it, was just over half, or 51%. By 2017 this proportion had risen – 68% of the 605 million people in need were getting the drugs they required.

The success is due, in large part, to the commitment and leadership of the WHO Regional Director for Africa, Dr Rebecca Matshidiso Moeti, who set up a dedicated project in the regional office called the Expanded Special Project for the Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases (ESPEN) which has been working with countries, providing technical and implementation support.

But despite these successes, the number of countries in Africa that are being validated by the WHO for achieving elimination of these diseases is still far below the rest of the world.

There is real potential for Africa to take leadership in this area and succeed. Unless this is done, NTDs will continue to cause pain, disability, disfigurement and stigma for millions of people in Africa, and will continue to rob developing economies of billions of dollars-worth of productivity gains.