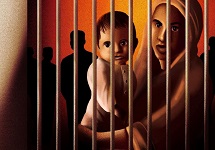

Saudi authorities are forcibly returning hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian migrants after arbitrarily holding them in indefinite detention in inhuman and cruel conditions including beating and torture solely because they do not have valid residency documents, a situation exacerbated by Saudi’s abusive kafala system, Amnesty International said today.

The organization is calling upon the Saudi authorities to investigate cases of torture as well as at least ten deaths in custody between 2021 and 2022. The new briefing, “It’s like we are not human”: Forced returns, abhorrent detention conditions of Ethiopian mçigrants in Saudi Arabia, details the situation of Ethiopian men, women and children arbitrarily held in the overcrowded Al-Kharj and Al-Shumaisi detention centres in dire and abusive conditions and forcibly returned to Ethiopia between June 2021 and May 2022.

“Since 2017, Saudi Arabia has arbitrarily detained and forcibly returned hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian migrants in conditions so abusive and inhuman that many developed serious long-term physical and mental conditions as a result. Now, more than 30,000 Ethiopian nationals are detained in those same conditions and are at risk of facing the same fate. Just because a person does not have legal documents does not mean they should be stripped of their human rights,” said Heba Morayef, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa.

“Saudi Arabia has been aggressively investing in re-branding its image as part of its ambitions to attract foreign businesses and investors, but beneath this glitzy veneer is a story of horrific abuse against migrants who have been toiling away to help Saudi Arabia realize its grand vision.”

There are an estimated 10 million migrant workers in Saudi Arabia. Amnesty International chose to focus on the situation suffered by undocumented Ethiopian migrants in Saudi Arabia due to plans announced in March 2022 by Ethiopian and Saudi authorities to return at least 100,000 Ethiopian men, women and children back to Ethiopia by the end of 2022 .

Between May and June 2022, Amnesty International spoke to 11 Ethiopian migrants who were detained in Saudi Arabia before being forcibly returned, as well as a family member of a former detainee, humanitarian workers and journalists with knowledge of the situation inside the migrant centres.

Amnesty International confirmed the location of Al-Kharj and Al-Shumaisi detention centres through satellite verification, and geo-verified videos from inside both centres, which reveal the dire conditions of the facilities.

Forced returns

Since 2017, Saudi Arabia has ramped up the arrest and forced returns of Ethiopian migrants as part of a crackdown on undocumented migrant workers in the country. Under Saudi Arabia’s abusive “kafala” system, undocumented migrant workers often have no pathway to regularizing their residency, and even documented workers risk losing their legal residency if they leave abusive employers.

In March 2022, the Ethiopian authorities announced that they would cooperate in the repatriation of over 100,000 of their nationals detained in Saudi Arabia by the end of 2022. Today, at least 30,000 Ethiopian migrants remain detained in Saudi Arabia solely for lack of legal residency and continue to suffer in overcrowded detention centres.

Faced with indefinite arbitrary detention under abusive conditions, with no recourse to challenge their detention, many of the detained migrants felt they had no choice but to agree to return to Ethiopia.

It is Amnesty International’s assessment that the migrants’ coercive environment makes it impossible for them to make a truly voluntary decision in line with the principle of free and informed consent, and that their returns to Ethiopia amount to forced returns. The Saudi authorities’ failure to ensure a case-by-case assessment of any potential protection needs of the detained migrants also creates the risk that individuals will be returned to face abuse, a breach of the principle of non-refoulement.

‘Inhuman’ conditions

The Saudi authorities have violated the basic principle under the Nelson Mandela Rules of treating prisoners “with the respect due to their inherent dignity and value as human beings.”

Former detainees interviewed by Amnesty International described overcrowding and the unsanitary conditions in both Al-Kharj detention centre in Riyadh and Al-Shumaisi detention centre, near the city of Jeddah, as “inhuman”. They recounted torture and beatings, and said there was inadequate food, water, bedding and no access to adequate medical care, including for children, those who are pregnant or severely sick.

Amnesty also found that unaccompanied minors and pregnant women were among those forcibly returned. Bilal, a former detainee held in Al-Shumaisi detention centre for 11 months, said he shared a room with 200 other people, yet there were only 64 beds. Detainees had to take turns sleeping on the floor. He told Amnesty International: “It is like we are not human.”

Mahmoud, another detainee who was held in both detention centres, said their daily food allowance was barely sufficient for one person.

Two other former detainees said the authorities gave each detainee just half a litre of water per day, despite persistently scorching temperatures in the overcrowded facilities.

Inadequate healthcare, death and disease

All former detainees told Amnesty International that the spread of lice and skin diseases were rampant. They also said that when lice spread among the migrants, they had to purchase plastic trash bags to use as blankets for protection and burn the hair off their scalps to remove the lice, because the authorities offered no other treatment.

Two humanitarian workers told Amnesty International that a significant number of people who were returned to Ethiopia from Saudi Arabia’s prisons suffered from respiratory and infectious diseases such as Tuberculosis.

Amnesty International also documented cases of deaths in custody in the Al-Kharj and Al-Shumaisi detention centres. Former detainees reported ten deaths between April 2021 and May 2022, many of which occurred after the denial of critical medical care, including in one case after injuries sustained from beatings. Amnesty International is calling on the authorities to investigate these deaths in custody and to what extent they are linked to the denial of adequate medical care.

Mahmoud, a former detainee who shared a cell with a man who was vomiting blood, said the authorities had only offered him paracetamol. The man died the day he arrived back in Ethiopia after being forcibly returned.

One video, verified by Amnesty International, shows a group of men gathered around what appears to be a body wrapped in a plastic bag, as the men perform salat al-janaza, a Muslim funeral rite.

Beatings and torture

Six former detainees told Amnesty International they suffered beatings and torture, including being beaten with metal sticks and cable wires, slapped in the face, punched, and forced to stand outside in extreme heat on asphalt roads until their skin burned.

The detainees said they were tortured after they protested the conditions of their detention, or when they tried to get medical attention for a sick cellmate.

Hussein, a former detainee, said a fellow cellmate died after the two of them were beaten: “He had pain in the ribs and was not taken to a hospital. We begged prison guards to take his body after he died…They took out his body two days later.”

“Saudi Arabia is one of the richest countries in the world, yet it is cramming migrants in dirty detention centres and refusing to provide them with proper medical care, food, and water. The ongoing abuse, in some cases leading to deaths of migrants, signals the unwillingness of Saudi authorities to improve the treatment of migrant workers. The authorities must urgently investigate the deaths and torture of detained migrants. Better still, they should stop detaining them in the first place,” said Heba Morayef.